Gitanyow and Nisga’a had a long-standing peaceful relationship as neighbours for thousands of years prior to European contact. Post-contact, their relationship is damaged due to territorial disputes.

What happened?

Many people remain unaware of the origins and implications of this overlap. In this presentation, we’ll delve into Gitanyow’s early ties with the Nisga’a, explore historical records, examine the lead-up to the signing of the Nisga’a Final Agreement, and establish the government’s role in perpetuating competing land disputes and inter-nation conflicts.

GITANYOW - WHO WE ARE

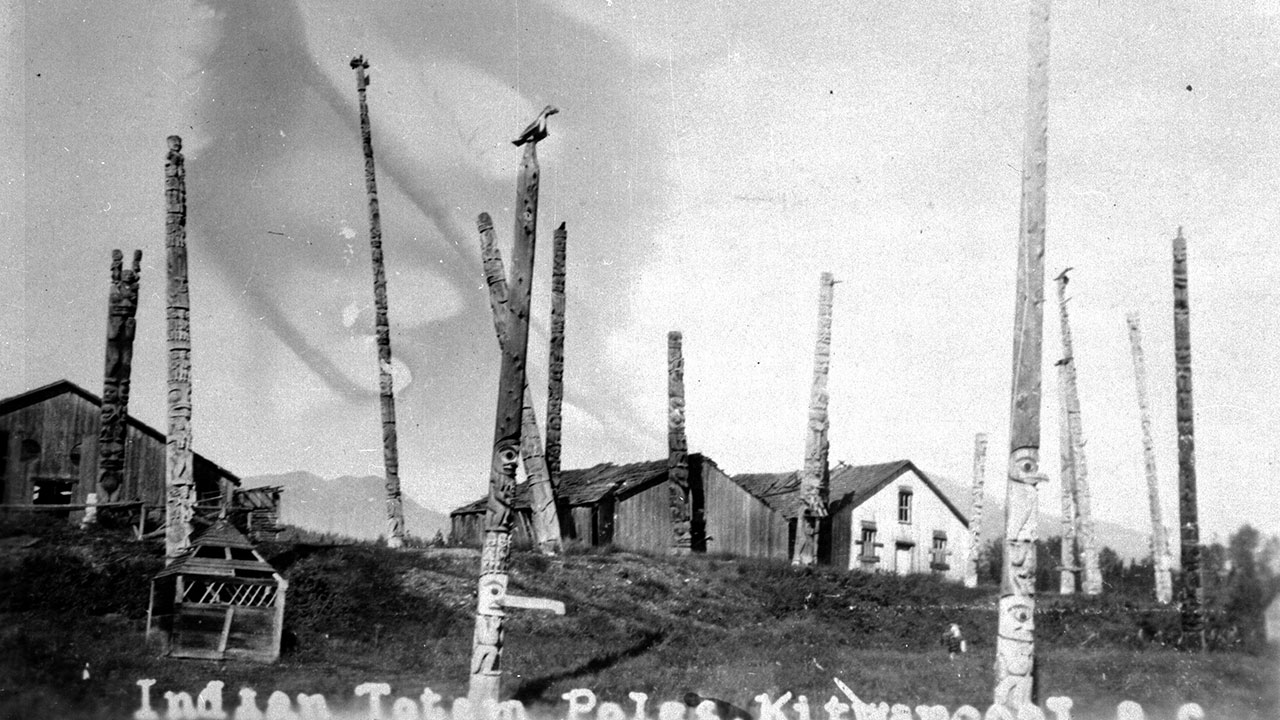

Gitanyow Nation is part of the larger Gitksan Nation in Northwest British Columbia. The historic village of Gitanyow, formerly Kitwancool, is home to some of the province’s oldest-known and most extensive collections of totem poles.

Totem poles are known as Git’mgan in Gitanyow’s traditional language of Simalygax and each acts as a memorial that depicts the family history of the Simogyet (Hereditary Chief) and Wilp (House Group) and represents a deed of title proclaiming inherited rights to specific lands and resources.

Gitanyow hereditary names have power and authority over traditional Gitanyow territories and carry important lineage to the past. Hereditary name holders share their name with a succession of matrilineally related predecessors, stretching back to historical events that describe the origins of the name and the Wilp they belong to.

All Gitanyow people belong to a Wilp, and membership is passed through the mother’s line. Each Wilp member receives a traditional name in the Feast Hall that is thousands of years old.

EARLY RELATIONSHIP

Before contact, Gitanyow and Nisga’a shared a peaceful history as neighbours with a well-established geographical boundary for thousands of years.

Gitanyow and Nisga’a shared the same matrilineal hereditary Wilp system and the Feast’s legal and political system. *Where your mother is from is where you are from.

Gitanyow and Nisga’a have many family connections.

Gitanyow and Nisga’a had an economic relationship through the Oolichan Grease Trade, which firmly connected the two nations.

In the 1800s, Gitanyow even assisted the Nisga’a in a war with another nation intruding on the southern portion of Nisga’a lands.

Today, Nisga’a and Gitanyow are politically at odds.

How did things change so fast?

MCKENNA-MCBRIDE ROYAL COMMISSION

In 1912, the McKenna-McBride Royal Commission (MMRC), a joint federal and provincial commission, aimed to address the “Indian land question” in British Columbia.

Its mission?

Convince First Nations to accept the reserve system that was born out of the Indian Act. The government believed that if additional reserves were set aside, First Nations would be satisfied, curbing further land and title rights disputes with Canada.

The six-man commission travelled across the province from 1913 to 1916, engaging with numerous bands and documenting their territorial claims. These historical records remain accessible today and are an integral part of this presentation.

MIGRATION & IMMIGRATION

1881 Canada Census – Gitanyow Population 211

1915 Canada Census – Gitanyow Population 46

Where did all the Gitanyow go?

In the late 1800s & early 1900s, many Gitanyow people moved to Nisga’a communities to work in canneries and join churches.

Some of these families eventually moved back home to Gitanyow, but many ultimately immigrated with the Nisga’a.

Gitanyow people living in the Nisga’a village of Aiyansh participated in the MMRC in Aiyansh but were testifying on behalf of Gitanyow territories, not Nisga’a territories.

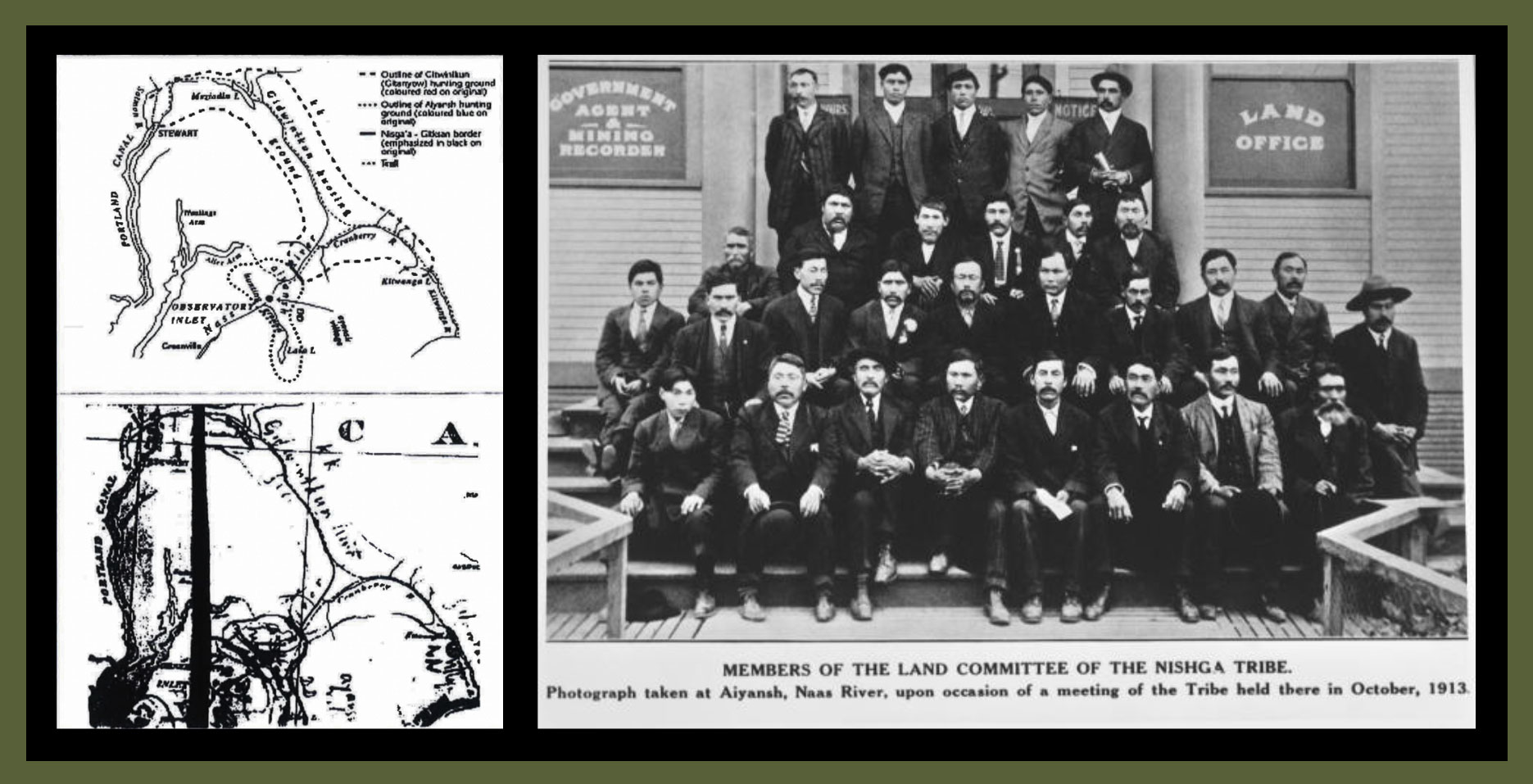

Nisga’a established their Land Committee to campaign for recognition of territorial rights.

Gitanyow people living in Aiyansh were part of early versions of the Nisga’a Land Committee and also backed early versions of territorial Nisga’a Gitksan Land Petitions.

During this time, Gitanyow hereditary names began being passed down in the Nisga’a Nation.

Was this the beginning of the overlap between Nisga’a and Gitanyow?

GITANYOW BORDER

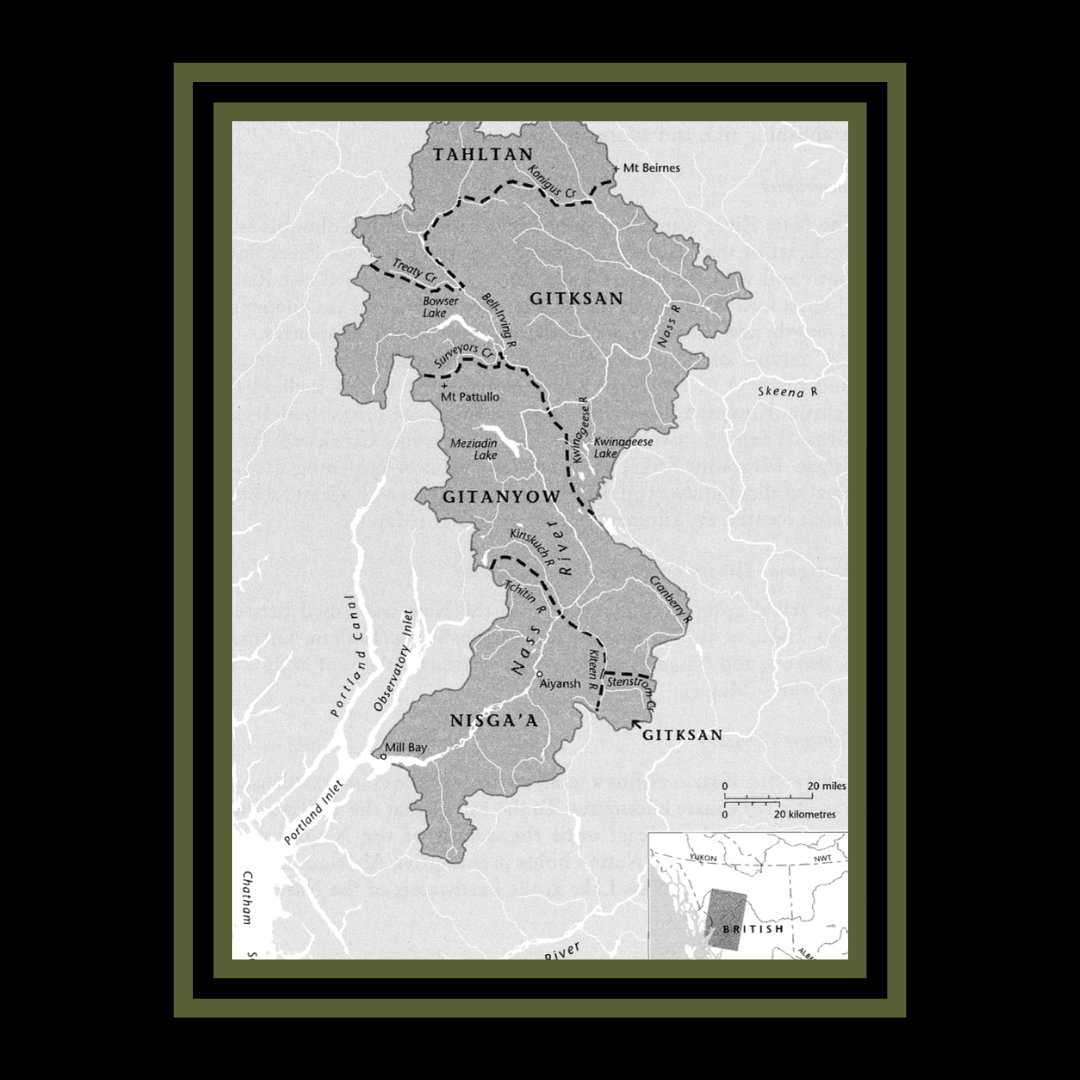

The earliest map of Gitanyow territory, drawn by a Gitanyow chief in 1875, was followed by more elaborate maps between 1910 and the present.

The Gitanyow have been resolute in identifying their boundary with the Nisga’a for thousands of years; the middle Nass River between the Tchitin and Gitxsits’uutsxwt located downriver from Kinskuch River, about twenty-five kilometres north of Aiyansh.

The Nisga’a also drew maps at this time. We’ll examine what Nisga’a chiefs and leaders identified as their geographical boundary with Gitanyow below.

PETER NISYOK

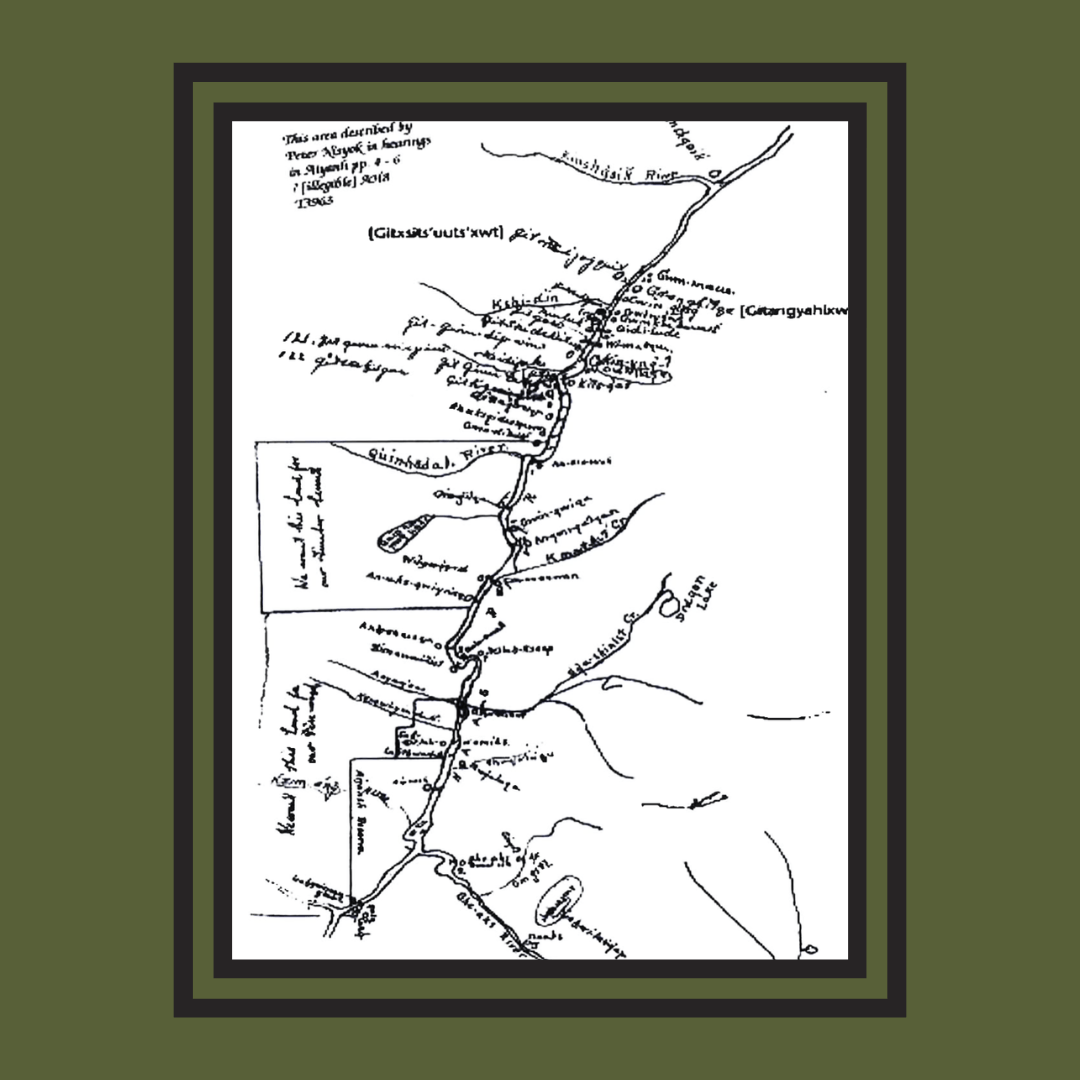

Peter Nisyok, a Nisga’a leader, was seventy years old when he made his statements to the McKenna-McBride Royal Commission (MMRC) in 1915.

Nisyok’s evidence included this detailed map listing place names along the Nass River from near the present-day village of Aiyansh to slightly above the confluence of the Tchitin River. On the map and in his statement are two place names – “gitksijo[s]qgwit [Gitxsits’uutsxwt]’ and “Git-anghilqa [Gitangyahlxw]” – at the ‘Kshi-din (Tchitin)” River, which shows that Nisga’a territory ends there.

Peter’s testimony supported Gitanyow’s description of our common boundary; this is the boundary that Gitanyow continues to honour today.

CHIEF SKADEEN

In his closing testimony, Skadeen said, “We already have a length of territory we require from a place called GITSIZUTQU [Gitxsits’uutsxwt] then it crosses the [Nass] river to a point known as GITANZALQ [Gitangyahlxw], thence down the river to a river known by the name of SIAKS [Tseaxr].”

“This was the territory that my uncle [Chief Sqat’iin] first worked over when the first surveyor visited us [in the 1800s] and when he left this world he left this [territory] in my hands and I hold it still … I don’t want the reserve.”

Skadeen’s evidence is very significant as he was a Nisga’a chief whose territory borders the Gitanyow on the Nass.

E.N. MERCER

Mercer was a representative at the MMRC hearings and a member of the Nisga’a Land Committee. His testimony sheds light on Gitanyow people who migrated to Aiyansh in the early 1900s and the war at Meziadin.

Mercer’s detailed account captures a period of change and coexistence.

“Some of the Gitwinlkun [Gitanyow] live at Aiyansh now, all the year around. They began to come at Aiyansh 15 years ago. Their hunting grounds is from that lake [Meziadin], down to the Nass River, also towards Gitwanga. The Gitwinlkun & Nass river people had fight Metsiadon Lake … the Gitwinlkul fought them, and since they won they kept that place for hunting. These people [at Meziadin Lake] were the Laxwiiyip.”

In 1916, Mercer, along with fellow Nisga’a Land Committee member Charlie Barton took their mission to Ottawa. Mercer’s detailed interview spans twenty-three pages, offering insights into Nisga’a villages, fish camps, Oolichan fisheries, and a map describing Nisga’a territories from tidewater to Aiyansh.

This map identifies the Nisga’a’s territory in the southern Nass watershed and outlines “Kitwanguun” territory in the middle Nass, including the Meziadin watershed. Mercer’s depiction of the Nisga’a – Gitanyow boundary aligns with Chief Skadeen’s and Peter Nisyok’s accounts from the MMRC hearings and Gitanyow’s historical description of our shared border.

WILSON DUFF

Thomas Berger, legal counsel for Nisga’a Nation, said regarding Duff’s anthropological evidence and claims, “Wilson Duff’s contribution was unique in Canada.”

Duff was a pioneer anthropologist and leading Northwest Coast specialist who, in the 1950s, studied the field notes and maps of Marius Barbeau and his associate William Beynon, who was Nisag’a. They had spent half a century researching the Tsimshian peoples, which includes the Nisga’a and Gitksan Nations.

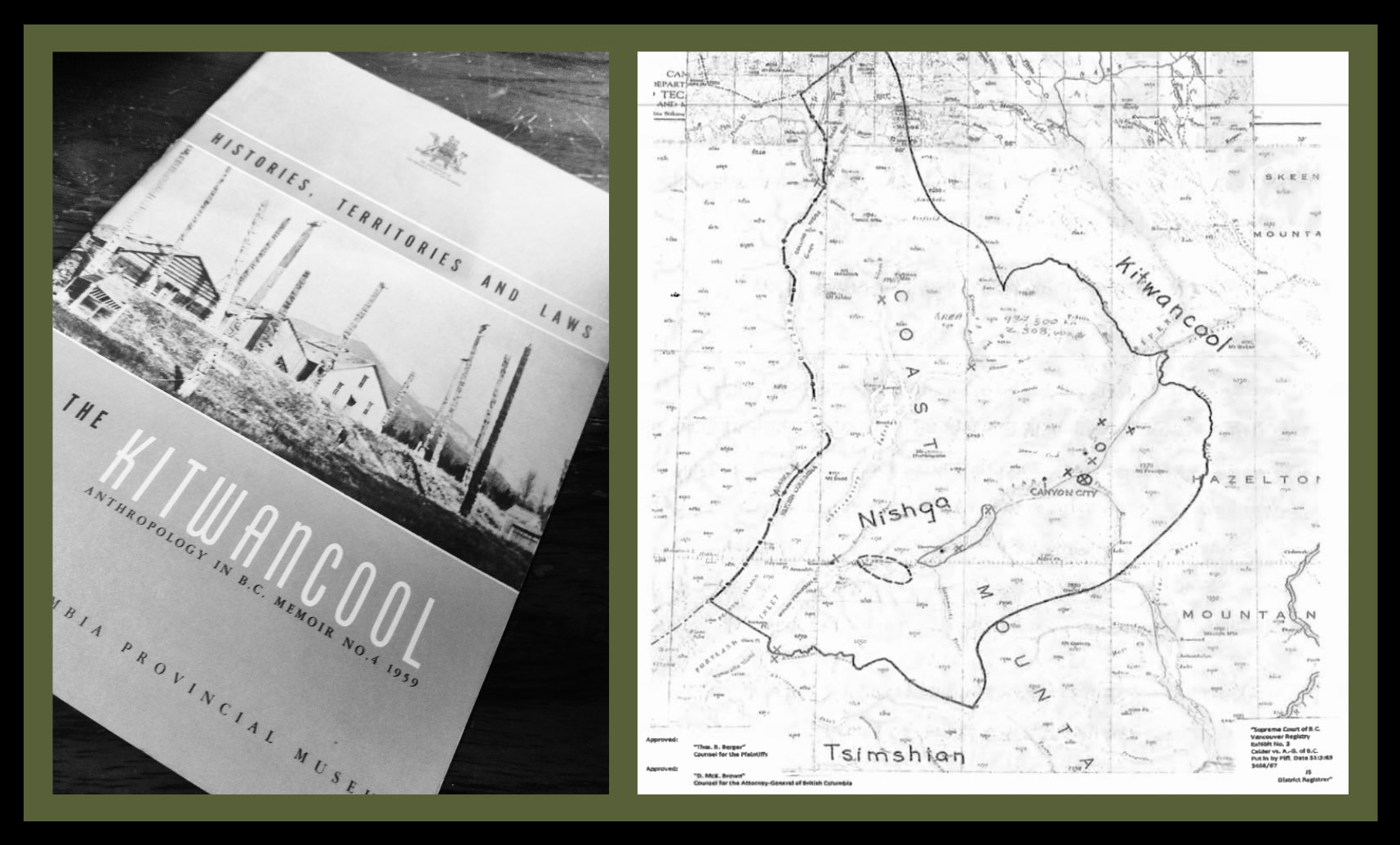

Wilson Duff had also worked with the Gitanyow and published their memoir in 1959, ‘Histories, Territories, and Laws of the Kitwancool.’

Duff’s evidence in the Calder Case included this map referred to as Exhibit 2, in which he portrayed the extent of Nisga’a territory, clearly showing that the Gitanyow bordered the Nisga’a on the lower Nass River.

When one reviews all of Duff’s work, including his un-contradicted testimony in Calder, he concluded that the boundary between the Gitanyow and the Nisga’a did not extend north of the Kinskuch River.

FRANK CALDER

Gitanyow people living in Aiyansh backed the Nisga’a, even providing funding to assist with the costs. However, they eventually withdrew their support when they realized Nisga’a was claiming Gitanyow territory. Gitanyow’s withdrawal of support was verified in 1995 by Frank Calder.

“During one of the campaigns for the Nisga’a and Gitksan Land Question Funds, Michael Inspring Bright collected from the Kitwancool people the sum of $140.00.”

“In 1926, when the village of Kitwancool decided to withdraw its support of the Land Question, it requested that the $140.00 which it had contributed to the Fund be returned to the Kitwancool.”

This historical record is essential as it shows that the Gitanyow did not consider themselves Nisga’a adoptees under the Aiyansh Constitution when it came to hereditary Gitanyow Lax’yip (Territory).

JAMES GOSNELL

“Whoever comes to [our] territory, we accept that, we accept that it is also in our testimony that… is finally written, they’ve got volumes and volumes of people of Kitwancool coming into our area. And were accepted and were adopted into the Nisga’a Nation. We have Kincolith and two-thirds of them are Kitwancool that are living in Kincolith right now.”

Although some Gitanyow people recently migrated and immigrated into Nisga’a communities, it does not mean Gitanyow lands went with them. The power and authority of Gitanyow Lax’yip (Territory) cannot be severed and remain with the proper inherited Gitanyow Chief name holders and Git’mgan (Totem Poles) in Gitanyow in accordance with Gitanyow Ayookxw (Supreme Law).

RICHARD & ARTHUR DERRICK

Richard, an elderly member of Gitanyow Wilp Gamlaxyeltxw, presented a map outlining their territories and connections to the land.

“[Our] families are living up there now at a place called Xsigiigyat – there is another place known as Xsimihlhetxwt/Derrick Creek … A little way up … I marked up to a place which is known as Winsgahlgu’l and from that point down on the river.”

His younger brother Arthur emphasized their continued connection to their traditional Gitanyow Ganeda (Frog) territories while living with the Nisga’a Nation.

“As you see … Richard Derrick is getting to be an old man and he is just speaking as a spokesman for our family, and I … stand behind him … second[ing] everything that he says … Gwinsgox [Kinskuch River] is the one we want as that is nearest to us here. It is over thirty years since we started living here in this village and all this time we have been going to this creek to get food for ourselves. As my brother told you he has brethren and relations and … uses the land further on for hunting, berries, fishing, etc. and I am very glad to have been able to tell you this.”

Nisga’a leaders witnessed the Gitanyow testimony on territorial claims in the Nass and did not contest it.

Five other Gitanyow people testified in Aiyansh about Gitanyow lands in the MMRC. Do you think submissions like the Derrick’s could have confused future generations of Nisga’a into blurring their interpretation of territorial boundaries with Gitanyow?

EXPANDING BOUNDARY

But in the 1960s, this changed. Since then, Nisga’a has expanded their boundary multiple times, while Gitanyow’s has remained consistent up to the present.

As this map points out, a small overlap on Gitanyow’s western border was first declared in 1969 during the Calder Case. Then, in 1983, while James Gosnell was President of the Nisga’a Tribal Council, Nisga’a extended their boundary further into Gitanyow territory.

After 1983, Nisga’a expanded their territory again, claiming the entire Gitanyow Nass territory up to Meziadin/Surveyor Creek, representing a whopping 84% overlap of Gitanyow territory. Nisga’a, with their final expansion to date expanded their boundary further northeast on the remaining Gitksan Wilp Nass territories, stopping at the Tahltan – Gitksan border of Treaty Creek.

The amount of land claimed by the Nisga’a increased nearly fivefold in thirty years. Their claim consistently expanded as they got closer to signing their treaty, with the final claim bearing little resemblance to the first.

Why do you think Nisga’a’s territorial borders continued to expand?

NISGA'A FINAL AGREEMENT

For the Nisga’a and government, its conclusion was a monumental legal and political event and the government poured millions of dollars into its promotion.

But the Gitanyow did not celebrate. First, three key policies harmed Gitanyow and other First Nations during the treaty-making process:

1. Canada only negotiated one treaty at a time, ignoring all overlap concerns, and Nisga’a was the first in line for negotiations.

2. There was no prerequisite for Nisga’a to prove the extent of their land claim nor to resolve the overlap.

3. B.C. publicly stated that they wouldn’t return more than 5% of traditional territory to be exchanged back to the First Nation in a treaty.

*This is highly significant as the Nisga’a greatly expanded their land claim closer to their settlement date, so the return of their true traditional territory would be more significant.

Second, although Minister John Cashore promised Gitanyow that the Nisga’a treaty would not impact hunting and fishing rights, the failure of the provincial and federal governments to respond to the many Gitanyow submissions on overlap had severe consequences:

1. Nisga’a were granted by the federal and provincial governments fee simple lands in Gitanyow territories.

2. They obtained fisheries management over the whole Gitanyow Nass territory.

3. A “treaty right to hunt” in the entire Gitanyow Nass territory.

4. An extensive commercial recreation tenure in Gitanyow territory.

5. They gained symbolic government recognition for their claim to the Nass Watershed.

6. And recently, the interpretation of the treaty was expanded, adding subsequent agreements that further harm Gitanyow.

Why do you think both levels of government overlooked Gitanyow’s concerns about territorial overlap?

WEAPON OF COLONIALISM

Now that we’ve explored the details of the overlapping territories between Gitanyow and Nisga’a, we ask a critical question: Are these overlaps a weapon of colonialism?

We sure think so. The Crown and industry use unclear territorial boundaries to:

1. Avoid establishing proper relations.

2. Justify minimal efforts to recognize rights and title.

3. Support outcomes that may infringe on the rights of some First Nations. This includes practices such as in the British Columbia Treaty Process, negotiating without due consideration of Indigenous connections to the land.

The result is delayed reconciliation and perpetuating conflicts, uncertainty and confusion on the land base for the nation and 3rd parties, and often expensive court battles.

COINCIDENCE OR STRATEGY?

The consequences of disregarding traditional laws and rights have had long-lasting effects that the people of Gitanyow have felt and could feel for generations.

Playing out in Gitanyow and Nisga’a today is a real-time crisis that can potentially cause further damage to the peace and order of Gitanyow Nation, create confusion, and threaten Gitanyow’s ability to protect their traditional lands.

A Gitanyow Wilp member residing in a Nisga’a community has recently claimed the Gitanyow hereditary name Wii Litsxw in the Nisga’a feast hall, which goes against Gitanyow’s traditional laws and the Nisga’a’s and is akin to identity theft.

As mentioned earlier, hereditary names are attached to specific pieces of Gitanyow Lax’Yip (Territory), and the Wii Litsxw name is tied to Meziadin in the heart of the Nass and Gitanyow’s traditional territory. The true Wii Litsxw living in Gitanyow lawfully inherited his name from his Uncle Morris Derrick in 2012.

This blazon act comes at a critical time for both Gitanyow and Nisga’a. Gitanyow Nation will take Canada to court for Aboriginal title on October 1, 2024, for recognition as the rightful title holders to their traditional lands. Also, the Nisga’a Nation recently applied for an environmental certificate for their proposed floating LNG facility, Ksi Lisims; the pipeline for the massive project aims to run through Gitanyow Lax’yip.

Is the timing of stealing Gitanyow’s traditional names a coincidence or a deliberate strategy?

Governments and big industry often seek individuals who echo their objectives which resembles an effort to undermine Gitanyow’s authority over their Lax’yip.

Gitksan Elders have long warned of cunning shapeshifters known for impersonating identities: the Wetsxw (Otter).

One traditional story tells of a young Gitksan man tricked by a Wetsxw while alone on his trapline. After days on the Lax’yip and missing his new bride, the young man’s mind wandered to his wife.

Elders cautioned Gitksan people to have clear minds and strong hearts as the Wetsxw can transform into the image of people’s thoughts and to be on guard for the one who covers their mouth.

But the young man forgot his teachings and was delighted when he saw who appeared to be his beloved wife approaching him, holding her hand over her mouth. She was actually a Wetsxw and it eventually possessed the young man.

When a Wetsxw is in transformation, they cannot hide their teeth, exposing them as an imposter.

As Gitanyow’s resilience is put to the test, we remind all to beware of the one who covers their mouth.

*For more details, please see our Open Letter to Calvin Morven.

STILL WAITING

Gitanyow and Gitksan asked for a mediator to review the issue, but the Nisga’a rejected all requests. The Nisga’a had no motivation to mediate once B.C. and Canada signed the Nisga’a treaty.

Decades later, little has changed. Gitanyow continues to pursue a mediated discussion between Nisga’a, B.C. and Gitanyow. More than 20 years have passed, and Gitanyow is still waiting to discuss both Nations’ futures in the Nass.

SUMMARY

By delving into historical records, we’ve seen the earliest documentation of what Nisga’a leaders declared as their territorial boundaries, which were in line with Gitanyow’s. Since then, Gitanyow’s territorial claim has been consistent, whereas Nisga’a’s have expanded multiple times.

There are crucial lessons to take from the Nisga’a treaty experience. The treaty-making process should take direction from the Supreme Court of Canada Tŝilhqot’in Aboriginal title case decision by implementing the test for title in order to substantiate boundaries. Territorial overlaps must be resolved before entering into treaty negotiations and, finally, a binding third-party process when Indigenous parties cannot resolve an overlap.

We hope this series serves as a reminder that acknowledging history, respecting rights and traditional laws, and working together toward peaceful resolutions are the only paths to coexistence and reconciliation.